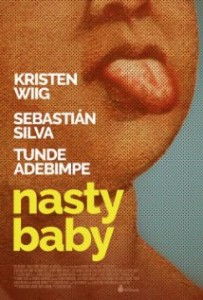

Kristen Wiig and Sebastian Silva star in “Nasty Baby.”

Going into Nasty Baby, the new sort-of-comedy from Sebastián Silva, I was under the assumption, based on a short press release I had read, that I was about to watch Baby Mama crossed with Modern Family, with maybe a splash of faux seriousness, a la Silver Linings Playbook, but starring Kristen Wiig. Nope. Not at all, not even close. And while the movie I just described would be a lot easier to watch, and would probably do well at the box office, Nasty Baby, which many viewers may well hate, accomplishes what films do so infrequently–it left me uncomfortable and puzzled in a productive way.

The basic plot here is simple. Polly (Wiig), and her gay BFF Freddy (Silva) are trying to have a baby. Turns out, his sperm count is low, so they convince his boyfriend Mo (Tunde Adebimpe) to be the donor. They all stroll around Fort Greene, gawking at multi-racial babies and imagining themselves as the perfect post-racial, all-inclusive, multi-culti, perfectly modern messy family.

Played straight, this is a saccharine plot at best, the kind of depiction of Brooklyn that makes half the country view the borough as a modern day Sodom and Gomorrah, the other half long to move here (until they discover that Freddy and Mo’s one-bedroom apartment in a brownstone would likely run them upwards of $3,500 a month).  But from the shaky hand-held camerawork to the weirdly intimate moments (despite a number of scenes in which either Freddy or Mo masturbate for sperm collection purposes, the closest the movie comes to any actual sex scene is Freddy giving Mo an assist during one such session) there’s an unsettling feeling that permeates throughout.

But from the shaky hand-held camerawork to the weirdly intimate moments (despite a number of scenes in which either Freddy or Mo masturbate for sperm collection purposes, the closest the movie comes to any actual sex scene is Freddy giving Mo an assist during one such session) there’s an unsettling feeling that permeates throughout.

In the opening scene, in which a fey gallery owner visits Freddy to discuss a performance art piece he’s working on, Freddy proposes a scenario in which he’s filmed naked, acting like a baby as an exploration of vulnerability and humiliation. Though intellectually intriguing, it becomes clear as he acts it out, that this is an aesthetic nightmare. That tension forms the backbone of the movie.

Unsurprisingly, Freddy’s project goes badly. That failure though, pales in comparison to the way his relationship with a local crank devolves. A man who calls himself The Bishop (Reg E. Cathey who you’ll recognize from The Wire and House of Cards), lives in the garden-level apartment of a neighboring brownstone. He’s definitely not all there, and might be harmless–selling stolen items on his stoop and hustling neighbors out of spare change by “helping” them park their cars–until he develops a fixation with Polly, which in turn fosters a weird, angry obsession on Freddy’s part. There’s a supremely uncomfortable moment where Freddy, Mo and some friends set off a smoke bomb, a joke gift given to Mo for his birthday, under Bishop’s stoop, then watch in horror as several people who are living in the cramped apartment, including a small child, come running out in terror. A cop later explains that the building is about to be sold and soon Bishop and his dependents will be gone. It’s a sharp nod to gentrification in Brooklyn, and to the truth that even as homophobia and other forms of discrimination have eroded, there’s less and less space in the city for the poor and frankly, the crazy. By the end of Nasty Baby it’s an open indictment of the type of progressive identity that permeates places like Brooklyn and San Francisco, rewarding ourselves for ousting homophobia and racism in such a way that ignores our own privilege and the price other, poorer, less visible communities pay for our cute coffee shops and live-work spaces.

If you’ve read about Nasty Baby at all you know that there is a sudden plot twist toward the end, a grand spoiler that entirely changes the film you’ve been watching. It’s true that the shift in tone is abrupt, and the series of events is tensely horrible in a way that borders on unwatchable. There’s so much foreshadowing, however, that anyone who has ever written a five-paragraph essay can see something dark coming from the first 10 minutes of the movie and make correct guess at a rough outline of what is likely to happen.

As a whole, Nasty Baby inversely mirrors Freddy’s relationship with the gallerist, who calls him out for promising a deeply introspective, revealing work and delivering a flippant, surface-level farce. What at first glance seems like an easy-going comedy reifying what we already think about people we know and like, is actually a darkly revealing look at truly, whose lives matter in the modern world.

Nasty Baby starts at IFC Center on Friday, Oct. 23.