As soon as the summer sun starts to scorch the Brooklyn pavement, Coney Island resurrects itself for another season of screeching rides and mischievous amusements as thousands migrate to its beach and boardwalk. While the former “Sodom by the Sea” has lost much of its old luster and seen significant changes in recent years, Phoenix-like rebirths are nothing new to the seaside escape—it has literally and figuratively risen from ashes throughout its storied history.

The age of amusement

Coney Island’s reputation as the most-famous of American beachfronts started in 1829, with the construction of the Coney Island House, accessed by a carriage road of crushed shells for upper class visitors. Increasingly opulent hotels, including the Oriental Hotel with its stately minarets, Brighton Beach Hotel, and Manhattan Beach Hotel, rose along the shoreline as Coney Island cultivated an air of exclusivity. With the opening of the New York and Manhattan Beach Railway and steamship service, wealthy New Yorkers sped to Coney Island to partake in the newly fashionable saltwater bathing, sporting flannel and wool swimsuits.

In 1875, Andrew Culver combined several rail lines into the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad, and the ease of transportation drew weekend crowds in the tens of thousands. The 300-foot-tall Iron Tower, then the tallest structure in New York City, was one early amusement. Culver erected it in 1876, having acquired it from the Pennsylvania Centennial Exhibition. The tower had a steam-powered elevator to whisk visitors up to a panoramic view.

Nearby was a curious kiosk called the Inexhaustible Cow, which offered five-cent glasses of iced milk squeezed from the udders of a mechanical cow by a team of dairymaids. The Seaside Aquarium opened in 1877 and exhibited oddities, sea specimens and a collection of exotic animals including giraffes and performing horses, as well as a pair of conjoined human twins.

The insatiable demand for amusements led to a long line of rides, parks, and performers. The first roller coaster was introduced in 1884: the gravity-powered Switchback Railway. Its popularity and technological innovations led to a rumbling army of coasters on the Brooklyn coast. The worst accident occurred in 1910 when 16 people were catapulted from the Roosevelt’s Rough Riders ride from a height of 30 feet, killing three. Then, traveling acts like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show swept in, and Harry Houdini gave his first Coney Island performance in 1891.

Sodom by the Sea

The Gilded Age saw the rise of a tawdry district known as West Brighton, developed under the corrupt guidance of John McKane, a developer who schemed to be named Commissioner of the Common Lands, giving him control over all construction. Starting in 1878, the Iron Steamboat Company brought West Brighton visitors to the new Iron Pier, its narrow walk packed with seedy hotels, saloons, and music halls.

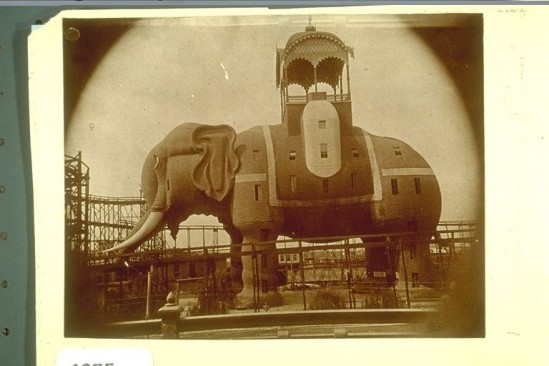

Soon enough, West Brighton helped cement Coney Island’s reputation as a “Suburb of Sodom,” as the Reverend A.C. Dixon put it, or, more popularly, as “Sodom by the Sea.” The most subversive strip was known as the Gut, and its icon was the Elephant Hotel, a 120-foot-tall elephant built by James Lafferty in 1885 with blue tin skin and glass eyes that gleamed in the night and offered ocean views through its irises.

The hind legs had spiral staircases up to the 31 rooms in the torso, and the front legs contained a cigar store and diorama. The phrase “seeing the elephant” was adopted to mean you were up to no good in Coney Island, and at one point a roller coaster raucously circled the massive metal beast. The hotel, like much of Coney Island, had a short life, and burned down in 1896 after being abandoned.

Nearby, a strip of alley known as Coney Island’s Bowery also gained a reputation for its bacchanalia, with freak shows, lurid dime museums, shooting galleries, and burlesque, all cultivated by George Tilyou.

For the unfamiliar, Tilyou was the son of Peter Tilyou, who ran the family-friendly Surf House. Neither were fans of McKane, and George would be the only person to testify against the corrupt developer in his first trial, leading to the loss of the Surf House and exile of both Tilyous from Coney Island until McKane was finally sentenced to six years in Sing Sing in 1894.

Throughout these years, gambling was Coney’s king vice, with three horse racing tracks in the area earning Brooklyn the title of America’s racing capital. That pony-playing reputation ended in 1910 when government regulations curtailed gambling at the races, taking much of the fun out of the sport.

The oceanside carnival

After being ostracized, George Tilyou would go on to influence the tone of Coney Island just as much as McKane by opening Steeplechase Park. Steeplechase—The Funny Place, as it was advertised—was not the first amusement park at Coney Island, though.

That distinction goes to Sea Lion Park, which Paul Boyton, a famed swimmer who had crossed the English Channel in an inflatable suit, opened in 1895 as a walled amusement area with a single ticket for entry. The aquatic-themed park featured the Shoot-the-Chutes, a toboggan that raced down ramps into a lagoon; performing sea lions; and a ride called Cages of Wild Wolves; as well as Boynton himself, posing in the inflatable suit. Inspired, Tilyou opened Steeplechase Park two years later, with more elaborate and physical rides.

You entered Steeplechase through the Barrel of Fun—a revolving cylinder that passed beneath the park’s emblem Funny Face, that vaguely sinister, widely smiling man whose visage still haunts the Coney Island boardwalk.

Strangely, there was a booth where visitors could rent clown suits and mingle with the park employees who were garbed in animal costumes. The most popular ride was the namesake Steeplechase, in which visitors rode four mechanical, life-size horses on a track circling the glassed Pavilion of Fun. On exiting, the riders were suddenly on a stage where air vents blew up the ladies’ skirts and the men were menaced by a clown who chased them into a corner of barrels piled precariously high, or to a box from which a devil’s head popped out. The audience, comprised of previous riders, all laughed uproariously at what they themselves had just experienced.

During this period, fires were not uncommon at Coney Island, thanks to flimsy park construction and ocean winds, and when one burned much of Steeplechase Park, the enterprising Tilyou offered admission to the smoldering ruins for 10 cents, quickly earning enough to rebuild.

After he died in 1914, the park was continued by his sons—the Parachute Jump, originally constructed for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, still stands today now painted in a glossy red. For 28 years, riders experienced free-fall from its radiating crown. The park met its demise in 1966, when Fred Trump, who planned to build high rises on the land, threw a party for its demolition. Guests received bricks to throw through the glass windows of the Pavilion of Fun. While the high rises were never built due to zoning changes, the land was revitalized by the Brooklyn Cyclones’ baseball stadium, which opened in 2001.

The next attraction to capture the public’s imagination was Luna Park, which opened in 1903. Frederick Thompson and Elmer Dundy purchased Boyton’s Sea Lion Park and tore all of it down, except for the lagoon, around which they built an elaborate architecture of spired buildings. The spectacle’s centerpiece was the Trip to the Moon ride, in which the airship Luna III took 60 passengers on an astral journey. The park included a variety of bizarre, dreamlike experiences like a trip to the North Pole, a ride that had its own ice manufacturing facility, and transported guests on an underwater journey to visit mermaids then up to the Aurora Borealis at the pole.

Meanwhile, at Dr. Martin Couney’s Infant Incubators, guests could, for 25 cents, view premature babies cared for in the facility, a free service that was supported by the exhibit cost.

There were also daily processions and many performing elephants, including Topsy, the notorious pachyderm who was electrocuted by Thomas Edison for the killing three trainers (one of whom had fed her a lit cigarette). The “electric Eden” of Luna Park was draped in over 200,000 lights, glowing at night like a mirage. The park closed in 1946 after an economic decline fueled by several fires.

Dreamland, which opened in 1904, was the last of the sprawling amusement parks, but it was the most ambitious. It was opened by Tammany Hall businessman William H. Reynolds and featured a French Renaissance-style, white and gold motif, although many of its rides were pale imitations of those at Luna Park, lacking Luna’s captivating whimsy, even if they were greater in size.

Still, the monumental park had some originality, including its chariot races and attractions like Little Hip, the world’s smallest performing elephant. Its main tower was 375 feet tall, which became a pillar of flame visible from Manhattan during a fire in 1911 that destroyed everything in Dreamland. A crowd of thousands looked on and recoiled in horror when a lion named Black Prince lurched from the flames, fire engulfing his mane and blood running from his fur. Police shot him with 60 bullets as he staggered through the park, and one policeman had to end Black Prince’s life with an axe. The brutality of the day condemned Dreamland to memory and added a dark footnote to Coney Island’s history.

A working class escape

By 1923, when the 84-foot boardwalk opened, Coney Island had become the weekend escape for the working class in New York’s sweltering tenements. Three subway lines converged at the ocean, the aristocratic wooden hotels of the 19th century had long closed, and the area was an escape accessible to all. With subway fare at a nickel, Coney Island became known as the “Nickel Empire.” The Wonder Wheel, still spinning in colored lights today, opened on Memorial Day in 1920. The Roaring Twenties also saw the birth of the Cyclone coaster in 1927.

Coney Island’s massive popularity continued after World War II, but when home air conditioners and automobiles became widespread in the late 1940s, its crowds receded, the decline accelerated by transformative city planning by Robert Moses, who was not a fan of Coney Island, considering it an unnecessary, over-commercialized zone.

One of Moses’ first acts was to put up stark “NO” signs listing things that were not allowed on the beach, including “peddling,” “dogs or fires,” “bicycling,” “roller skating,” “vehicles other than baby carriages & wheel chairs for invalids,” “newspapers other than for reading,” “sitting on rail or steps,” “bathing rings, rafts, inflated or buoyant,” “throwing of missiles or sand,” and “kites, flags or pennants.”

Amusement areas were rezoned for passive recreation, and between 1960 and 1973, 15 towering housing projects and apartment buildings soared up to loom over the remnants of Coney Island. Federal funding that was supposed to finance more buildings disappeared, leaving vacant lots of rubble from structures that had been torn down in anticipation. Moses also exiled the New York Aquarium from Battery Park to Coney Island in 1957, where it was built over the former location of Dreamland.

During the 1980s and 1990s, increased crime and beach pollution did nothing to improve Coney Island’s image (neither did the urban dystopia depicted in The Warriors). Yet, it kept going, with visitors arriving, albeit in reduced numbers, each summer. The Moses-era zoning regulations were finally reversed and several community groups worked to improve the area while preserving its character.

Among them was Dick D. Zigun, who founded Coney Island USA in 1980—it continues to operate out of the former Childs Restaurant building on Surf Avenue. The 1917 terracotta building maintains Coney Island’s history museum and hosts freak shows and strongman competitions that bring back some of the old spirit. Zigun also founded the famous Mermaid Parade in 1983.

Two large companies, Zamperla and Thor Equities, now own significant parts of Coney Island, and Zamperla opened a new amusement park in 2010, resurrecting the name, if not the freewheeling weirdness, of Luna Park.

Although little remains of its old splendor and strangeness, a stroll down the boardwalk past the Parachute Jump, the whirl of lights from the Wonder Wheel, and the screams from riders on the Cyclone still recalls a bygone era. Coney Island holds onto an intangible quality—it’s a mythical place, with gauzy visions of lost amusements parks and hordes of beach goers who first strolled onto the sand in wool bathing gowns. While its popularity as a tourist destination may wax and wane, among similar sandy strips of coastline, Coney Island is unparalleled in the realm of the imagination.

great piece. thanks

that was an amazing article. i have been reading about coney island for years and that article put it all in a nutshell. thanks!

Hi, great site. I have some real Coney Island trivia questions that I need factual answers for. I hope maybe you or someones visiting in your site can help. Murray Zarret of Animal Nursery rented out the Steeplechase pavilion for a summer season after Steeplechase official closed. what year was that? 1965 or 1966? Sometime in the mid-1960’s a drunken man climbed to the top of the parachute jump and did a very daring King Kong act as police tried to talk him down and TV helicopters circled overhead. when did this UNFORGETTABLE event happen?

I remember another drunk man climbimg the parachute in the 80s

I have a memory of the aurora borealis in Sea Gate sometime in the 1940’s—Does anyone else have a memory of that?