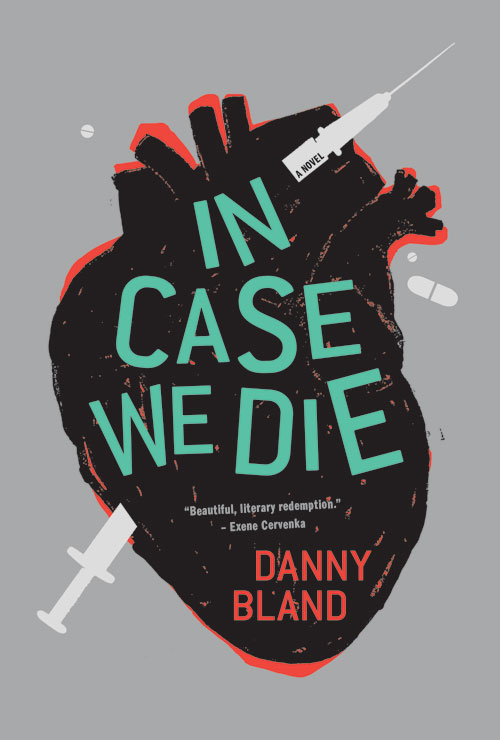

Were there a checklist of the things most likely to make me interested in reading a particular novel, Danny Bland’s In Case We Die, would have more checked boxes than any novel in recent memory. Drugs: check. Funny and unique sexual situations: check. A punk rock angle: check. Street life and hustling: check.

Plus, Bland’s novel has two wild card factors that make it alluring–Fantagraphics Books a killer publisher that rarely does novels of this sort I’ve sung their praises here before for their beautifully laid out comic and photography books.

The second wild card factor? Blurbs like no other book. If you think that cover blurbs aren’t that important for a book’s success, you couldn’t be more wrong. For a perfect example take, The Contortionist’s Handbook, which became a cult classic on the strength of its own merit. However, who would have picked up the book by the unknown author in the first place if not for the glowing blurb by then rare-blurber Chuck Palahniuk? Bland’s book has blurbs by the elite of the tattoo rocker badass community including porn star John Doe, punk pioneer Wayne Kramer of MC5, Duff McKagan of Guns ‘n’ Roses, and death row-survivor-saint Damien Echols. Apparently, the audiobook version of the novel will include chapters read by the above blurbers, as well as Aimee Mann, Mark Maron, and others.

However, while all this adds allure, none of it addresses the question of quality. None of these blurbers are novelists. In essence neither is Bland, or if he is, In Case We Die is his trial run. Bland has been a member of numerous punk bands, most notably The Dwarves, a band whose vocalist Blag Dahlia also recently stepped into the role of novelist

Put simply, In Case We Die is a heroin novel, the story of Charlie Hyatt, a sex store worker whose past is dotted with drugs and debauchery. We follow him into detox for heroin addiction and relive his tales of woe during the withdrawal process. I enjoyed this method of story telling. When a person goes from blissfully feeling nothing, to complete raw exposure to the world, to complete physical and psychic pain, memories are likely to feel more vivid than waking life, and it’s through this lens that we follow Hyatt’s war stories. There are moments of lightness in the book as well: a customer from the sex shop offers Hyatt money to sleep with a peep show dancer in the back of his car. Hyatt discovers his dying neighbor’s painkillers and bonds with him over jazz music and morphine and it mixes nicely with kind of misery endemic to these types of novels.

I must admit that I truly disliked this book for the first few pages. I found the language showy, detached and sophomoric. I’ll never accuse a person of trying too hard-I don’t believe in chastising effort–but sometimes it takes a lot more of it not to fill your sentences with flashy words. Somehow though, that jarring writing style calms down as the book moves forward. In a few chapters, my gripes fell to the wayside. This book is not going to land Danny Bland in the same category with William S. Borroughs, Alexander Trocchi, Jerry Stahl and Eddie Little (this list is a great jumping off point for anyone who wants to immerse themselves in the cannon of “Opiate Fiction”) but it’s enjoyable, if you enjoy utter pain and sadness, and it takes you on a ride. So for a first novel it’s a job well done.