From the opening of Books are Magic, author Emma Straub’s new bookstore here in Brooklyn, to the slew of excellent memoirs, novels and non-fiction works released in 2017, it’s been an incredible year for books. Here are a few that we particularly enjoyed, three of which happen to touch upon mental illness in some way. This is either a total coincidence, or a reflection of these crazymaking times.

Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America’s Most Storied Hospital, David Oshinsky

Ok this one technically came out in November of 2016, but I’m guessing that its release may have been overshadowed by the news cycle, so I’m going to go ahead and include it here. Anyone with an interest in New York history is going to love this thorough, but very engaging account of Bellevue from its early days as an almshouse up through the dramatic post-Sandy evacuation. The public hospital has been a crucial city service since before there really was a city, and it has played a role in every major medical event and development, including the Civil War, the development of evidence-based medicine, and the AIDS crisis, in the history of the United States. –Annaliese Griffin

Ok this one technically came out in November of 2016, but I’m guessing that its release may have been overshadowed by the news cycle, so I’m going to go ahead and include it here. Anyone with an interest in New York history is going to love this thorough, but very engaging account of Bellevue from its early days as an almshouse up through the dramatic post-Sandy evacuation. The public hospital has been a crucial city service since before there really was a city, and it has played a role in every major medical event and development, including the Civil War, the development of evidence-based medicine, and the AIDS crisis, in the history of the United States. –Annaliese Griffin

Manhattan Beach, Jennifer Egan

I can’t remember the last time I fell so hard for a novel. Manhattan Beach is the kind of book that will make you miss your subway stop. Set mostly in New York City during World War II, this is a wartime drama with nary a soldier in sight. Three storylines weave together—Anna Kerrigan, a young woman working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, her father Eddie and a high society gangster named Dexter Styles. Anna is the novel’s beating heart and as her quest to become a shipyard builder takes her into the East River, the building energy in the city takes her across it into Manhattan. Egan is a meticulous researcher and reading about the city during this period, especially what the Navy Yard was like at peak production, is almost as satisfying as tracing the narrative threads as they combine, unravel and come back together again. —A.G.

I can’t remember the last time I fell so hard for a novel. Manhattan Beach is the kind of book that will make you miss your subway stop. Set mostly in New York City during World War II, this is a wartime drama with nary a soldier in sight. Three storylines weave together—Anna Kerrigan, a young woman working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, her father Eddie and a high society gangster named Dexter Styles. Anna is the novel’s beating heart and as her quest to become a shipyard builder takes her into the East River, the building energy in the city takes her across it into Manhattan. Egan is a meticulous researcher and reading about the city during this period, especially what the Navy Yard was like at peak production, is almost as satisfying as tracing the narrative threads as they combine, unravel and come back together again. —A.G.

Gorilla and the Bird: A Memoir of Madness and a Mother’s Love, Zack McDermott

When I read Zack McDermott’s essay “The ‘Madman’ is Back in the Building” in The New York Times this fall I knew I needed to read his memoir, Gorilla and the Bird. McDermott was living in Manhattan and working as a Legal Aid attorney in Brooklyn when he experienced a total psychotic break. For an entire day he raced around Manhattan, convinced a film crew was capturing every move for the pilot of a brilliant comedy he’d write and star in. He ended up in Bellevue with a bipolar disorder diagnosis.

McDermott makes this more than a memoir about his several breaks with reality, he also details what a powerful force his mother is in his life. And indeed, “The Bird” as he describes her seems like one of the single toughest women you’re ever likely to meet. This doesn’t devolve into maudlin, “my mom saved my life and now I’m grateful” territory, nor does it fall into the trap of advocating that mental illness can be loved away. It’s just a beautifully written, often painfully funny story about how life is hard, but that can be okay, too. —A.G.

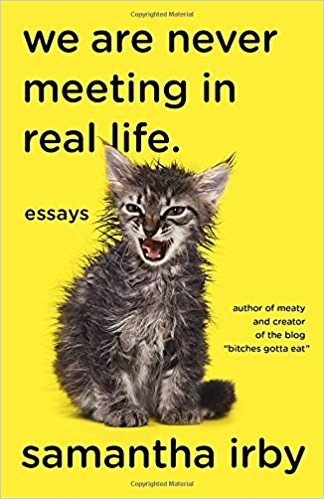

We Are Never Meeting in Real Life, Samantha Irby

I have a big confession to make about this book–I totally judged it by its cover. I wasn’t familiar with Irby or her blog, bitches gotta eat, and I just assumed this was a standard issue, “all my friends get married and make me wear terrible dresses in their weddings while I have so many hilarious romantic foibles of the online variety” essay collection. That could not be further from the truth and I’m so glad that I actually opened this book and read some of Irby’s deeply funny, ridiculously smart writing.

I have a big confession to make about this book–I totally judged it by its cover. I wasn’t familiar with Irby or her blog, bitches gotta eat, and I just assumed this was a standard issue, “all my friends get married and make me wear terrible dresses in their weddings while I have so many hilarious romantic foibles of the online variety” essay collection. That could not be further from the truth and I’m so glad that I actually opened this book and read some of Irby’s deeply funny, ridiculously smart writing.

Irby presents herself as a prickly fuck-up who doesn’t really fit in anywhere, but this book is also a sweet love story (with strap-ons) and a non-saccharine tale of becoming unexpectedly okay with yourself. She might prefer the couch, takeout and reality television to human contact, but Irby has a piercing insight into her own life and motivations. She endured a pretty dismal childhood, marked by illness, poverty, violence and the death of both her parents in her late teen years, and her complete lack of sentimentality about her life, coupled with a willingness to be completely open about it, manages to be funny, painful and original all at once. And, if you think the way that Lena Dunham writes about sex is some real talk, please pick this up and get ready for some real, real talk.—A.G.

Unbelievable: My Front-Row Seat to the Craziest Campaign in American History, Katy Tur

In 2015, a time that now seems like another planet, Katy Tur was happily living the life of a London-based foreign correspondent for NBC. At the beginning of this brisk, riveting memoir, Tur is enjoying weekends at her boyfriend’s in Paris, reasonable English work hours, and an upcoming vacation to Italy, when her boss calls her to suggest a few days following the Trump campaign, which then seemed like a joke. Covering Trump was supposed to be a lark, a way to dip her toe back into American politics, to explore career options beyond the London stint. Instead she was forced out of her comfortable European correspondent life into a haunted house of a campaign, during which the future leader of the free world would refer to her as “third rate,” and insist on calling her “little Katy.”

Tur’s TV news style makes for crisp, incisive observations. The book flips back and forth in time between election night, back to her first Trump rally, and around again to every rally, plane fight, press conference, and email exchange with the likes of Hope Hicks and Sean Spicer in between. She makes herself relatable, though she didn’t need to (the candidate certainly wasn’t), but her descriptions of the grind of campaign life, the fast food and long hours and lonely hotel rooms gently pierce the veil of glamor surrounding TV personalities. Tur takes readers behind the scenes of live television, of writing scripts and questions, of what it’s like to chase after candidates in search of the perfect quote, the perfect shot.

Her style makes the content a little easier to go down. She’s also the person who’s covered Trump the longest, the one who quickly grasped that he could win, and perhaps one whose insights can help us deal with him now that he’s here.—Ilana Novick

Mental, Jaime Lowe

My work life briefly intersected with a really sharp writer, Jaime Lowe, who happens to be bipolar. I didn’t realize what that actually meant for her until I read her New York Times essay about a manic episode that was laugh-out-loud funny, until it wasn’t, and how lithium saved her, until it didn’t. She delves deeper into the reality of living with the disorder in her memoir, Mental, and if you thought your twenties were hard, figuring out who you are and what you want, having bipolar disorder on top of that typical soul seeking is even more surreal. Her escapades are many—she spends time in the kitchen of Noodle Pudding, boxing at Gold’s Gym, and jumping from magazine to magazine like a real-life game of Frogger as the industry burns down. In trying to parse just how big of an impact being bipolar has had upon her life and personality, though, it’s hard to separate the fact that she is also a journalist, and immersing yourself in new and strange worlds comes with the territory. When she discovers that the lithium she has been taking to normalize her all these years is harming her physically, she goes on a spirit quest before she weans herself off of it, to the source of the largest lithium deposit in the world and the largest mine in the U.S., to the lithium-filled springs her grandfather soaked in in Germany, and finally to a conference in Rome to meet the most prominent psychiatrist studying bipolar disorder. They are like talismans she needs to touch before she ventures into her new normal, with a new drug. It’s a provocative journey that deepens your understanding of mental illness and what it’s like to depend on just the right pills.—Nicole Davis

The Epiphany Machine, David Burr Gerrard

If a machine could look deep into your soul and tattoo a message of your essential being onto your forearm, would you give it a go? And what would that message say? These are among the lighter questions raised by Queens-based author David Burr Gerrard’s second book, The Epiphany Machine. The darkly funny and surreal story follows Venter Lowood and his tangled relationship with this sewing machine-like device that tattoos personalized revelations on its users’ forearms, administered from an Upper East Side apartment by a cult leader or a charismatic prophet, depending on your stance. These epiphanies have a profound effect on the users’ lives, and the story takes a political pivot after the events of 9/11 when the authorities start demanding the epiphanies are stored in a database to preempt future attacks (particularly pertinent in this moment when government attempts to counter terrorism could undermine our online privacy). From a brilliantly bizarre premise, Gerrard grapples with issues of collective accountability in a time of terror, digital surveillance, and group think, all while keeping us completely gripped in a very human story. I felt angry, hopeful, indignant, and sad at turns, and ultimately complicit.—Tyler Wetherall

Too Much and Not the Mood, Durga Chew-Bose

This book of personal essays—a collection that is poetic and sharp by quick turns—comes from Durga Chew-Bose, a Canadian writer living in Brooklyn. In prose that is ecstatic (and only occasionally, bloated), Too Much and Not the Mood contains the author’s eloquent musings on subjects ranging from heartbreak, (“Heart Museum”) to “growing up brown in mostly white circles,” (“Tan Lines”) to the Silver Screen heroes of Hollywood’s first Golden Age (“Summer Pictures”). Chew-Bose’s essays are structurally unusual and driven by voice; she often hangs a right where you expect a left, and almost never resolves her own intellectual knots. Her overstuffed essays are accordingly thrilling, craft-wise—though this style is on best display in the memoir-adjacent pieces, like the central piece in the collection, “Heart Museum.” This dizzy, dancing inventory of objects, people, and experiences the author has loved could be a LiveJournal entry in lesser hands. But Chew-Bose’s “Museum” has the scope and elegance of a literary Louvre.

This is the kind of book best enjoyed by a sentence-lover. One who underlines, texts friends quotes, makes meals of that casual epiphany. Comparing Chew-Bose to other poetic nonfiction writers like Amy Leach, Wayne Koestenbaum, or Hilton Als therefore feels apt. There is something of Annie Dillard in her handling of words, too. Metaphors and modifiers are her diamonds. She loves words, and that makes you love hers.—Brittany Allen

The Abundance, Annie Dillard

If you’ve ever taken an intro to essay writing class (something of a niche market, to be fair), you’ve probably already run into the work of Annie Dillard, who is a grand master of the form. In this new collection of her “narrative essays old and new,” Dillard’s best work (and some of her odder, ambitious, but-still-amazing work) is gathered and arranged in streamlined fashion, creating the perfect starter kit for the new-to-Annies of your acquaintance. The Abundance‘s best gift to the reader may be its structure. The way this collection lumps essays from Dillard’s already published work (Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Teaching a Stone to Talk) into organized, mostly chronological thematic chunks provides useful readerly scaffolding for essays that already like to meander and drift. It’s an especially well-curated collection, too, including greatest hits like Dillard’s essay “Total Eclipse,” and thrilling B-sides like “Waking Up Wild.”

Dillard’s tone and style is philosophically driven. Under the guise of narratives about, say, unlikely members of the animal kingdom, she poses questions about the nature of human sentience, or how people ascribe meaning to natural phenomenon. But her sense of awe and delight in the world eclipses those few moments in the book when her writing feels heady. With poetic language and personal anecdotes, she tends to temper brilliance with accessibility. Consider this gem of an aphorism from that opening and damn-near-perfect essay: “Usually it is a bit of a trick to keep your knowledge from blinding you.” Dillard is one of those writers who never blinds, but always illuminates.—Brittany Allen