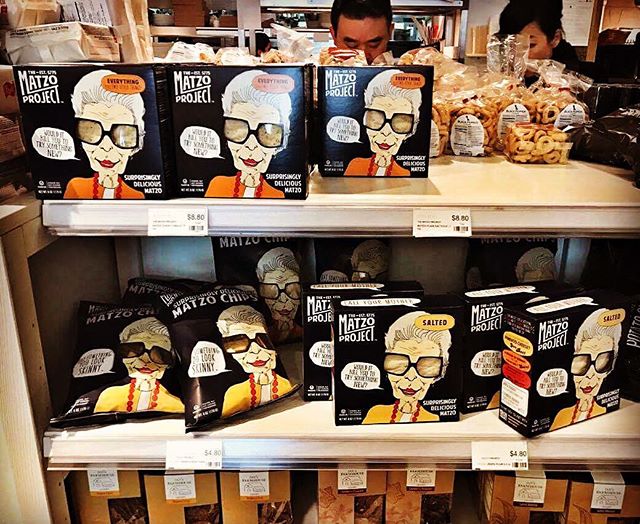

Last spring Matzo Project matzo was in three stores and sold out in a matter of hours. Now they’re all over the country, including at Eataly. Photo: Matzo Project

Passover this year begins on the evening of Monday, April 10 with seder. That’s two weeks away, and whether you’re an Orthodox traditionalist seeking out shmurah matzo for your Passover plate, or looking for a delicious Kosher-but-not-fully-Kosher-for-Passover alternative, you’re in luck. There are better matzo options than the supermarket stuff out there for you.

Brought to the forefront by young Jewish chefs like Yotam Ottolenghi and Michael Solomonov, who wrote the wonderful cookbook Zahav, Jewish cuisine is thriving right now, from dishes like brisket and matzo ball soup that are Eastern European in origin, to the vegetable and spice-heavy cuisine of Israel. Last spring Dan Barber, chef and local food advocate, had a long essay in The New York Times about what goes into making shmurah matzo. Around the same time The Matzo Project released a tiny batch of their delicious matzo to three stores in Brooklyn and Manhattan. It sold out within hours.

New York has seen Mile End Deli, Black Seed Bagel, Frankel’s and Seed and Mill Halvah and Tahini flourish over the past few years. Since their trial run for last Passover, The Matzo Project has blossomed into a full-blown business that has matzo and matzo chips on the shelves of stores in nearly two dozen states, and available for sale online, in plain (yes, there’s salt), everything and cinnamon and sugar. “We have scaled up and we’re ready to take on the pita chip.” says Matzo Project co-founder Ashley Albert.

Staying Kosher, but not Kosher-for-Passover (which would exclude salt and other flavorings), The Matzo Project joins Vermatzah, a Vermont-based matzo company that refers to their product as “eco-kosher” in a market that seems to have been underserved, judging from the enthusiastic reception.

It’s not just that we’ve reached such a fever pitch with food that we’re fascinated by the minutiae of even an item that traditionally has been most remarkable for its blandness. Matzo has the ability to simultaneously function as a delicious cracker at your cocktail party and as a symbol of Jewish history and culinary heritage. Try to achieve that with a box of Triscuits.

Shmurah matzo from Lubavitch Bakery in Crown Heights is a surprisingly great, if slightly shatter-prone, cracker if you add a little salt. Photo: Annaliese Griffin

Albert is perhaps the biggest advocate of the idea that matzo should become your new favorite cracker. “When I have a party, I get a pita chip for the hummus, a tortilla chip for the guacamole and a water cracker for the goat cheese, but you can use a matzo chip with ALL THREE,” she says. After last spring’s success, Albert and co-founder Kevin Rodriguez headed to the Fancy Food Show where they were inundated with orders. They then spent months finding a bakery with a direct-fire oven. Most commercial facilities use a convection oven for even heat, but uneven heat is exactly what gives matzo those brown bubbles that make matzo, matzo, says Albert. They’re now baking their crackers and chips at a facility in Sunset Park, with plans to add matzo ball soup mix, which will be vegan and all-natural (“It was ridiculously challenging to make that happen,” says Albert), as well as a variety of chocolate covered matzos to their product line later this year.

Albert and Rodriguez hope to liberate matzo from its place as a seasonal-only food, and plan to have their chips, crackers and other items on shelves year-round. Albert said that she had recently gone to a party where the hostess served a bag of her chips alongside a wide variety of other snacks, with no instructions. “She didn’t decant them into a bowl and it was fascinating to see what people did with them,” Albert says. Guests used the matzo for scooping up everything from guacamole to bean salad, to pairing with cheddar cheese.

Unlike the salt-loving Matzo Project products, Kosher-for-passover or shmurah matzo is made only from water and flour (acceptable flours include wheat, spelt and kamut). It must be unleavened to represent the Jews’ flight from Egypt, which took place with such haste that their bread did not have time to rise. This requires either a separate oven or a ritual cleansing of an oven in which leavened bread has been baked, prior to matzo production.

I purchased a box of shmurah matzo from Lubavitch Matzah Bakery in Crown Heights to sample the traditional version. You really notice the lack of salt when you eat it plain, but with anything only top, like hummus or goat cheese, it is a surprisingly great, if slightly shatter-prone, cracker. Jayne Cohen, Jewish food historian and matzo lover, said that after touring a shmurah bakery, and sampling matzo straight from the oven, she started adding olive oil and salt, and maybe a little rosemary at home, and then popping them back in a hot oven for a few minutes. “They were delicious, very hot, wheaty and toasty,” she says. “So now I heat them up for better flavor. It’s a very elemental cracker, just flour and water.”

While the concept of matzo as a cracker, and a flavored one at that, is new to the U.S. market, Cohen says that’s old news to the French.

“In France there is a mazto maker that is 100 years old, Paul Heumann, that makes unleavened crackers for everyday use from kamut and spelt, with flavorings like tomato and chestnut,” says Cohen. “You can find it in the big food section of the department store Bon Marche, and in the cracker department at the grocery story. The French food blogger Piment Oiseau, made an hors d’oeuvres that she called ‘tres girlie’ using their pink matzo, which is flavored and perfumed with beet juice, plus fromage frais and pineapple chutney.”

As a physical manifestation of the Jewish diaspora, matzo takes many forms around the world, including softer versions that use more water and come out more like flatbread than crackers, often found in Sephardic and other non-Ashkenazi traditions, Cohen says. Traditionally, matzo was only eaten during Passover, and was usually handmade by poor women or widows as way to earn a living. The process became mechanized in the early 20th century as companies like Manischewitz and Goodman’s Matzo, which started out in Pennsylvania and then moved to New York City, started to produce it in factories.

“Once it was made in quantity it became more of a year-round product,” says Cohen. “Goodman noticed that people would buy extra boxes to keep after holidays.” It was this surplus that led to familiar Jewish comfort foods like matzo ball soup and matzo brei. Italian Jews have long made a lasagna using matzo moistened with water or stock in place of noodles (there’s even a Martha Stewart version), and mina, a vegetable and matzo pie from Sephardic cuisine, has found its way onto Gwyneth Paltrow’s menu. A chocolate-caramel matzo crunch has become a popular unleavened Passover treat–The Matzo Project is also working on a s’mores-inspired treat with chocolate and marshmallow.

The possibilities for matzo stretch beyond the culinary.

Shmurah matzo is made in accordance with strict Orthodox rules.

Cohen says that some Christian congregations use it as the Eucharist, in the belief that it most closely approximates bread that Jesus would have eaten. She also noted that when Manischewitz was founded in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1888, their customers were not limited to the Jewish community. “It was a great substitute for hardtack,” she says. “Many non-Jews took it on pioneer-type trips into the West because it couldn’t go bad.” Some modern day preppers also stock up on matzo because of its longevity on the shelf–or in the fallout shelter.

Cohen assured us that although matzo is a food that is part of the ritual of Passover Seder, there are no rules forbidding non-religious consumption that she is aware of.

Albert says that in the process of researching and learning to bake matzo, she, as a mostly non-observant Jew, found a new sense of community, which while not religious in nature feels important to her. “I reconnected to Judaism in an interesting way that I didn’t anticipate,” she says. She suggested that the recent resurgence of Jewish delis in New York City is about celebrating tradition and identity through food, in an inclusive way. “It’s so surprising,” she says. “This is not particularly glamorous food.”

Cohen echoed that sentiment, “Food tells the story of Jewish history and life, and it’s wonderful thing to share with other people, whether they share the religion or not,” she says. “People who dismiss what you might call ‘kitchen Judaism,’ that’s ridiculous. Religion is a celebration of life and finding your own way to celebrate life with food is wonderful.”

A version of this story originally ran on April 18, 20016. It has been updated and revised for 2017. For the original version visit here.

This was a very interesting article. I was wondering whether we can visit the Brooklyn location where you produce your products. I am a member of a sisterhood that is affiliated with Temple Israel Reform Congregation of Staten Island. I would like to hear from you regarding a tour of the facility. Thank you.

Linda Kantrowitz Hanibal