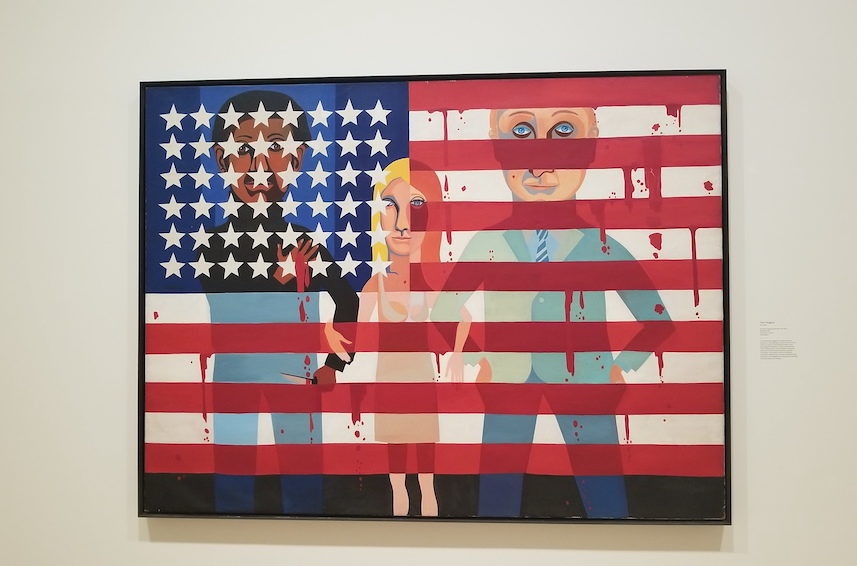

Faith Ringgold’s “United States of Attica,” part of Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition “Soul of a Nation.” The poster is a map of American violence, in the green, black and red colors that reference Marcus Garvey’s Black Nationalist Flag. Image courtesy Brooklyn Museum.

In 1966, Stokely Carmichael (now Kwame Ture), the national chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and a staunch adherent of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s nonviolent philosophy, coined the phrase Black Power after an especially harrowing student march that ended in Greenwood, Mississippi. Although both black and white conservatives and moderates were shocked by the Howard University undergrad’s subversive speech—Dr. King called it “an unfortunate choice of words—to some, it made a lot of sense. The laws that federal, state and local governments diligently crafted to deprive African captives of their basic human rights were expanded and strengthened during Reconstruction and solidified in later decades to more thoroughly disenfranchise all people of color from every aspect of society. They did this while turning a blind eye to the millions of African-American men, women and children who were terrorized, lynched, murdered, raped, unjustly incarcerated and driven from their homes.

In his 1968 book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, Mr. Ture defines Black Power as “a call for black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, to build a sense of community—it is a call for black people to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations.” His ideas echoed that of pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey, a proponent of black self-reliance. Impatient for immediate change in the wake of sweeping civil rights advances as injustice and institutionalized racism flourished, a younger generation embraced this phrase. It also took flight internationally with African revolutionaries and the separatist movement that ignited the African diaspora in the early 20th century was reborn. Black self-reliance was a key element that allowed for survival within an inherently racist system and literally, to paraphrase some old Southern black folk I know, made a way out of no way.

Mr. Ture’s impassioned call for Black Power gave way to the Black Arts Movement (1965 – 1975), a collective of politically driven black playwrights, visual artists, poets and musicians originated by poet, playwright and essayist Imamu Amiri Baraka. Atlanta’s National Black Arts Festival, founded around a decade later, was a direct result of the Black Arts Movement, and is now one of the most important festivals in the world that presents work from the African diaspora, featuring readings and literary presentations, theater, dance, visual art, a film festival and music of every genre. I grew up in Atlanta, in a completely African-American middle-class neighborhood. Thanks to initiatives set forth by Maynard Jackson—the first African-American mayor of Atlanta or any major city in the South—the arts flourished along with black-owned businesses. I was surrounded by cultural nationalism at a time when the Black Arts Movement had saturated our lives so thoroughly, the most ordinary moments were alive with a kind of grounded self-awareness and ennobled understanding that can only happen when full immersion in your history and your heritage is a way of life.

Brooklyn Museum’s current exhibition, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (1963 – 1983), encompasses the seismic and all-consuming political upheavals of these overlapping periods. As African-Americans attempted to live on ground that was even more unstable and incendiary than ever, visual artists of color were compelled to take action by creating work that elevated us as a people while speaking directly to an avalanche of societal ills that brought us to that moment. There is a fire, a fury, an intensity that shifts restlessly within each work, with an eloquence that is direct and unyielding, relentless in its uncompromising visage—and a tone that is unapologetic politically and culturally. The exhibit, which includes over 60 artists and more than 150 works of art, shows how the urge to make their message understood touched down like lightning and took root, expanding into several major cities in each region of the country, conjuring a cultural nationalist ecosystem—not unlike Atlanta with its National Black Arts Festival—that edified the community.

Faith Ringgold’s “American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding”(1967). Photo: Queen Esther

This is the artist as agitator, as teacher, as documentarian, as protester, as firebrand. Dana C. Chandler’s Fred Hampton’s Door 2 (1975)—an actual door painted green, trimmed in red and riddled with bullet holes—was created in the wake of the murder of the young Black Panther leader by the Chicago police. Inspired by the Black Arts Movement’s directive to depict the reality of the black experience honestly, Faith Ringgold’s “super realism” achieved this in a visceral way with the painting American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding (1967) wherein a white woman stands between a black and a white man—arms linked and all of them wounded and bloody—with a bleeding American flag as a backdrop. How curious that a black woman isn’t included in this tableau.

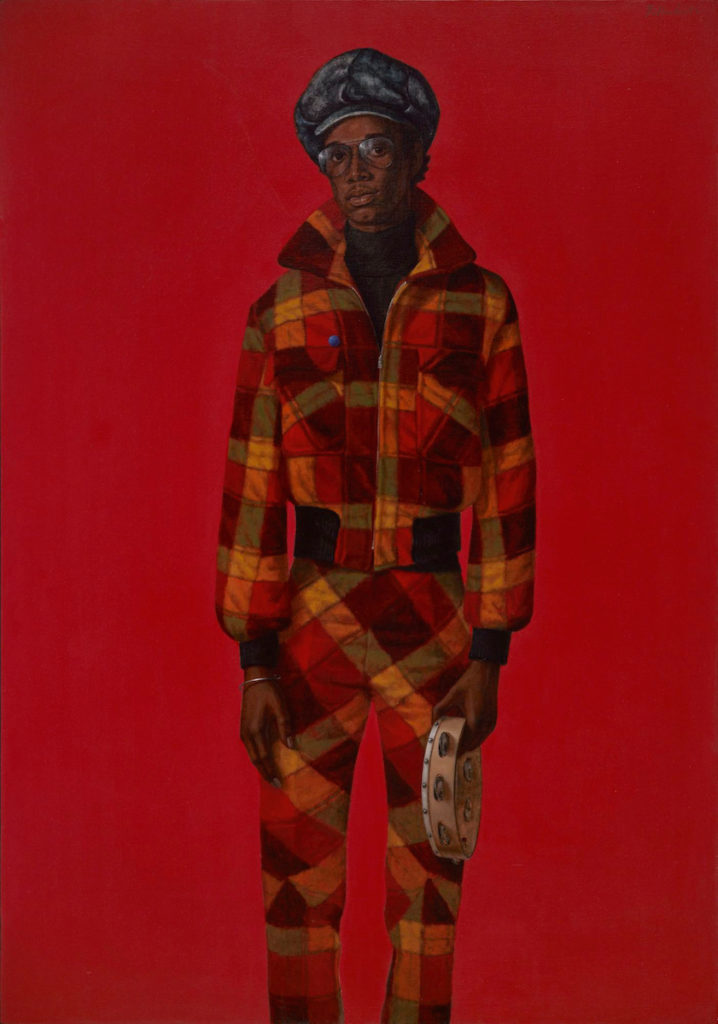

“Blood (Donald Formey)” by Barkley L. Hendricks, courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New york

Even when trends in the art world of the late 1960s shifted towards conceptual art and away from figurative painting, a work like Barkley Hendricks Blood (1975), with his black male subject’s steady unwavering gaze at the viewer—a deadly move for a black person in all too many instances in America—proves that although portraiture was considered too Eurocentric by his peers, placing the black body and black subject matter in figurative painting was in and of itself a revolutionary act.

Ultimately, this exhibit uplifted me tremendously because it brought me back to my Southern cultural nationalist roots, and it reminded me of the importance of Black Power and the Black Arts Movement, and how they enriched my life. I found myself wishing that everyone could see this art in a museum’s permanent collection, not as a part of a special exhibition that comes and goes and never returns. How much of the art in this exhibit is still straining to garner the same level of respect as their white peers?

“Fred Hampton’s Door 2” by Dana C. Chandler (1975), is riddled with bullet holes, a reference to the Chicago police raid upon the 21-year-old Black Panther leader’s home, where he was killed. Photo: Queen Esther

In this day and age, Black Power is a marketing ploy, its tropes and its imagery splayed out in Your Favorite Black Rapper and/or Pop/R&B Star’s video montage to distract you from sifting through their empty lyrics for a sliver of the feeling that will overwhelm you if you stand in front of Fred Hampton’s door. Perhaps someday, the reality of our present-day black experience will be depicted honestly in the art we enjoy. Until then, we can collectively stand at the threshold of a dream deferred—in awe of their rage, and ours.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power runs through Feb. 3, 2019 at Brooklyn Museum, before it moves on to The Broad in Los Angeles in March. There are a number of special talks and events planned in conjunction with the show, like the upcoming evening with Faith Ringgold on September 27.

I am constantly browsing online for posts that can aid me.

Thanks!

Some truly nice stuff on this website, I enjoy it.