Michael Sauter reads the latest edition of Akashic Books’ popular Noir series, and revisits the anthology that started it all.

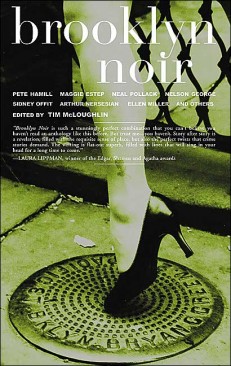

In its mere fifteen years as an indie publisher, Brooklyn-based Akashic Books has built up an impressively varied catalogue of titles, from Tom Hayden’s Ending the War in Iraq, to Michael Stipe’s “photo diary,” Two Times Intro: On the Road with Patti Smith, to the surprise best-seller, Go the F*ck to Sleep, Adam Mansbach’s so-called (and so funny) “bedtime book for parents.” But none of those books has done more to put Akashic on the map than its globally popular Noir series of short story collections–which began with 2004’s Brooklyn Noir and, in the seven years since, has included similar compilations from nearly every corner of the civilized (and not-so-civilized) world.

In its mere fifteen years as an indie publisher, Brooklyn-based Akashic Books has built up an impressively varied catalogue of titles, from Tom Hayden’s Ending the War in Iraq, to Michael Stipe’s “photo diary,” Two Times Intro: On the Road with Patti Smith, to the surprise best-seller, Go the F*ck to Sleep, Adam Mansbach’s so-called (and so funny) “bedtime book for parents.” But none of those books has done more to put Akashic on the map than its globally popular Noir series of short story collections–which began with 2004’s Brooklyn Noir and, in the seven years since, has included similar compilations from nearly every corner of the civilized (and not-so-civilized) world.

So far there have been volumes named for the obvious locales (Manhattan, Chicago, Los Angeles); the slightly less obvious locales (D.C., Texas, Mexico City); the who-knew locales (Cape Cod, Twin Cities, Richmond) and the far-flung locales (Haiti, Moscow, Mumbai, Copenhagen). But wherever Noir takes us, the concept always involves an anthology of tales that explore the grittier, seamier, darker shadows of whatever city/state/foreign land to which we’ve been transported.

Over the course of nearly 50 titles (and counting), the very idea of noir has expanded well beyond the Double Indemnity femme fatale and the jaded-but-romantic Philip Marlowe P.I. prototype. Most of the protagonists are, in fact, ordinary people from mundane walks of life, drawn by love, lust, greed, scorn, revenge or desperation, into breaking the rules just this once. But it isn’t always about murder. Sometimes, there isn’t even a gun.

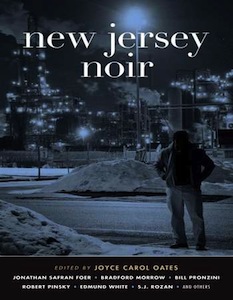

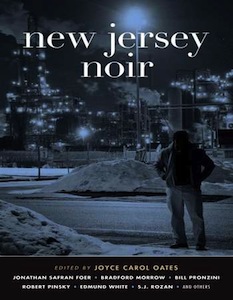

As redefined by the works in this series, noir is more than a style, or even a genre. It is a state of mind, a given of the human condition. As guest editor Joyce Carole Oates explains in her intro to the latest collection, New Jersey Noir, it’s also about a “fundamental betrayal of the human spirit–innocence devastated by the experience of social injustice or political corruption…” Noir, as she sees it, is “the betrayal of one’s kind.” Hence all the emphasis on the femme fatale–or as Oates calls her, “the primary Eve.”

There’s a classic femme fatale or two in New Jersey Noir. There’s also more than one poor, doomed male protagonist. But what makes this edition such a strong example of the noir aesthetic is the vividly imagined settings and situations that it finds for all its dark doings. There isn’t a story in New Jersey Noir that doesn’t grab and hold your attention. And while not all of them deliver on their initial promise, more than enough of them do. Pay-off or not, these stories aren’t just exercises in mood and milieu. They’re serious fiction, and the true gems among them are works of literary art. Which isn’t to say that some of those works of art don’t haul off and slam you in the gut, catching you wholly by surprise–even when you think you’re ready for it.

That’s what happens in Jeffrey Ford’s “Glass Eels.” You know that the make-money-quick scheme of two middle-aged losers is going to go bad long before they meet a man in a van behind a burnt-out roadside diner. But when the end comes, somewhere in the wild dunes of the Jersey Shore, it’s even worse than you were expecting. The same goes for Jonathan Santlofer’s “Lola,” in which a frustrated artist’s preoccupation with a pretty PATH train commuter turns him into a stalker, which inevitably leads to the fateful night when things go very wrong–again, not the way you were anticipating. It’s bracing the way this story’s turn of events snaps into place.

And then there are the stories that sneak under your skin, not so much punching you in the gut as eating at your soul. Jonathan Safran Foer’s “Too Near Real” is just such a story: In it, a guilt-ridden Princeton professor slowly balls himself up in a world of Google maps after being put on forced sabbatical for his affair with a grad student–who may or may not have committed suicide because of something he might have done. Or didn’t do. The details are deliberately sketchy, little more than allusions. Hints. But instead of frustrating us, these snippets of cause and effect keep us hanging on every word. We learn just enough of what’s locked away in this guy’s head to feel exactly how tragically haunted he is.

In the same spirit, though more direct in effect, is the collection’s finale, written by its editor, the estimable Ms. Oates, who once again demostrates her mastery of the form with “Run Kiss Daddy,” about a middle-aged man who’s getting a second chance with a second marriage, complete with a built-in second set of lovable kids–who will give him ample opportunity to get it all right this time. The preciousness of what he has, and how easily he could lose it, is evoked with a grim discovery, which calls up an even grimmer memory. Oates lets the moment come and go, fleetingly. It’s all the more disturbing that way.

* * * * *

Brooklyn Noir, the one that started it all, now seems somewhat raffish and rough around the edges in comparison to its bridge and tunnel counterpart–a mark of how good New Jersey Noir really is. But that doesn’t mean that it’s not full of pungently hard-boiled tales about bad things happening to not-so-bad people. And if some of its entries seem thematically overfamiliar or narratively underdeveloped, there are others good enough to merit inclusion in any collection of noir fiction–or for that matter, any collection of serious fiction.

I’m thinking about Pete Hamill’s “The Book Signing,” about an aging, best-selling beach-read author who returns to his Park Slope birthplace, where he finds the woman he long ago left behind, still waiting; Chris Niles’s “Ladies Man,” the story of a former foreign correspondent whose past inevitably catches up to him in Brighton Beach; and especially, Ellen Miller’s “Practicing,” the childhood memory of a self-loathing adult narrator, who recalls her singularly complex relationship with the single-parent dad who died on her too soon. Even if you’ve read it before, this story’s very last sentence still has the power to sting.

Some of the lesser efforts also have a way of sticking with you. There is Neal Pollack’s “Scavenger Hunt,” about a Coney Island carousel operator who gets taunted and teased into a humiliatingly compromising position by two calculating college hotties, and Norman Kelley’s “The Code,” in which a Prospect Heights gangsta rapper struts right into the hands of some shady music biz entrepreneurs with perverse plans for turning a profit off him. This isn’t the darkest story in Brooklyn Noir but it’s by far the most lurid: proof that noir comes in different shades of black, some of them as glittery as an oil slick–and just as toxic.

Brooklyn Noir 2 came out in 2005. Brooklyn Noir 3 came out in 2008. What is it about this borough that warrants three editions of heinous crime, while Manhattan and L.A. are stuck at two? Meanwhile, seemingly ripe cities like Amsterdam and Rio are still waiting for their close-up. Something tells me, though, that they too will get their turn. As New Jersey Noir decidedly demonstrates, this cool little series has a lot of life (and death) left in it yet.

Michael Sauter is a Brooklyn-based arts and entertainment journalist who has written about books for such publications as Entertainment Weekly and Publisher’s Weekly. He still hasn’t ruled out writing the Great American Novel, but isn’t holding his breath.

Note: Many of these books are also available as ebooks from Greenlight Bookstore, one of our sponsors.

My relationship with New Jersey Noir began at the Mysterious Bookshop, where Joyce Carol Oates introduced most of the contributors (Jonathan Safran Foer was notably absent). While it was intriguing to learn of each story’s genesis, my reading experience was at turns laughable and/or maddening, with the exception of Foer’s and Oates’ stories (and Oates’ outstanding introduction). I guess I couldn’t take many of the stories seriously, but then maybe that was the point. Learning to read noir in Brooklyn . . .