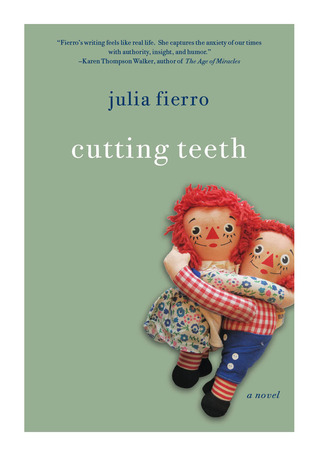

Julia Fierro’s debut novel, Cutting Teeth, is a vivid, wryly observed study of the hothouse of 21st century parenting.

You hear the phrase “long-awaited debut novel” thrown around a lot these days, which is ironic given that it’s become something of an oxymoron. More and more reliant on bankable household names to meet its meager bottom line, today’s book industry tends to be wary of the humble debut novelist. And the writers who do elicit genuine excitement are far more likely to be the precocious than the long germinating type. All of which makes Julia Fierro’s new book Cutting Teeth a rare literary beast—a first novel that’s been hotly anticipated by industry insiders for months, by an author who’s honed her craft for years. The heat surrounding Cutting Teeth can be chalked up in large part to Fierro’s subject: the trials and travails of modern parenting, an issue so relentlessly fascinating, so deliciously divisive that the book seems destined to land on sandy blankets across America this summer. But it’s safe to say that at least part of the interest surrounding the novel is due to the author herself. This may be Fierro’s first published novel, but she is no stranger to the publishing world.

If most of us struggling literary types fall squarely into either the MFA or the NYC camp these days, Fierro happily straddles both worlds. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the founder of Brooklyn’s own Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop, Fierro has emerged in recent years as a doyenne of the literary scene. Her social media conversations read like a Who’s Who of Literary America and her writing school (which, full disclosure, I’ve attended) has increasingly come to function as a sort of high-end clearing house for up-and-coming writers. Some of her recent instructors include Emma Straub of Laura Lamont’s Life in Pictures fame, critical darling Adam Wilson, and Ayana Mathis, whose novel The Twelve Tribes of Hattie was an Oprah Book Club 2.0 pick.

Given Fierro’s literary stature, some may find it surprising that this is her first novel. But it becomes easier to understand when you see how much energy she devotes to nurturing the talents of those around her. At a recent reading, Fierro was introduced as “the mother of literary dragons,” but it might be more accurate to call her Brooklyn’s literary fairy godmother. To those who know her she is a nurturing force: the first person to praise the work of promising newcomers, to dole out a much needed hug or to provide a key reference to an agent or MFA program.

Fierro’s ability to draw normally reclusive (or at the very least awkward) writers out of their shells and into conversation with one another begs comparison to another literary mother hen from a different era, Gertrude Stein. But unlike Stein, Fierro seems less concerned with reinventing the form than with stretching our sympathetic imaginations. This fierce urge to connect, which animates her life and teaching, comes through on every page of Cutting Teeth.

Set in Long Island, Cutting Teeth charts the mounting tensions between six Brooklyn parents (and one long-suffering nanny) marooned together in a ramshackle beach house for the weekend with their children. Over the course of the book, Fierro seamlessly shifts between one perspective and the next until her readers are close enough to recognize themselves in each. A literary dramedy about love and family and all of the fantastically messy stuff in between, Cutting Teeth has been dubbed “a Mommy book” by some, but it is better understood as a vivid, wryly observed study of the hothouse of 21st century parenting.

I spoke to Julia Fierro in early May about the genesis of her book, the taboo against overt emotion in literary fiction and the trouble with genres.

Orli Van Mourik: I happened to read Cutting Teeth around the same time that I picked up New York Magazine writer Jennifer Senior’s recent book All Joy and No Fun. When I finished them, the first thing I thought was: if my girls ever want to understand just how nuts the parenting atmosphere was when they were young, I will point them toward these two books. Senior’s book maps the sociological conditions that gave rise to our overdetermined brand of parenting and your book perfectly captures the emotional realities–the anxiety and self-castigation, the perfectionism and competitiveness.

I know you are the parent of two small children. Did you consciously set out to document our parenting culture, or did the book arise more organically out of your own experience?

Julia Fierro: This is the most wonderful compliment! I really admired Jennifer Senior’s book and felt her focus was very much simpatico (as my Italian father would say) with Cutting Teeth.

I sometimes wonder if I’ll always write about the same emotional topics—navigating relationships and friendships, maintaining self-esteem, managing self-scrutiny, fear, desire and existential panic, all that great messy emotional stuff that makes us human. But, I imagine I’ll filter it through the unique lens that intrigues me the most at that particular time in my life. When I was developing ideas for and then writing Cutting Teeth, the intense 24-hour hands-on parenting of young children was my reality. I was working out the definition of “woman” in that vulnerable postpartum stage of life—also the point in a woman’s life where the most is asked of her endurance.

Like many writers, I need to write to inform myself of myself. Cutting Teeth was a way for me to make sense of my own anxieties and insecurities as a young mother, as well as a way to remind me of my strengths as a parent. There is a part of me in every single character in Cutting Teeth, even the ones who appear as if we have nothing in common. The questions they ask themselves are questions I’ve asked myself many times. Am I a good enough parent? Partner? Person? How has my identity as a woman (or in Rip’s case, as a man) changed now that the world labels me a parent? Do I love my children enough? Can I make my children happy? Can I keep my family safe?

Cutting Teeth is a very personal book, although it is, of course, still heavily fictionalized, but the heart of the book (forgive the cliché) is mine, and the book did grow quite organically from my own experience. I already miss the purity in the process that was writing Cutting Teeth. I was writing to prove to myself, after a long break to raise my children and The Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop, that I could finish another novel, and so I wrote with a pure intention. I wrote to write. If I had truly believed that this novel, very much my own “parenting confession,” would actually be published and shared with so many readers, who knows if I would have been able to write with such honesty?

Your resume reads like Hannah Horvath’s dream diary. You were admitted to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop straight out of college and awarded one of the program’s coveted Teaching-Writing Fellowships for a short story you wrote during your first year. But this is your first novel. I’m wondering if you had any trepidation about telling the story from so many different points of view? Weaving in the perspectives of so many characters is no mean feat.

The comparison did make me laugh a little, because from what I know of Hannah Horvath, we have little in common. My parents were not ecstatic when my acceptance letter from Iowa arrived, and it took a lot to explain to them that it was a prestigious graduate program. I remember my father asking me, “Why can’t you go to journalism school, where you’ll have more chance of making a living?” Now, they are proud of me and very excited about Cutting Teeth.

Although Cutting Teeth is my first published novel, it is not the first I’ve written. I finished a novel while I was at Iowa, and another unfinished draft lingered in the years after. I’ve had many passionate one-night stands with opening novel chapters in the past ten years—only to wake up the next morning and pretend as if our affair never happened. Several people have asked me about the structure of Cutting Teeth, specifically how I kept “all those plates spinning,” meaning the multiple points-of-view, and all I can say is it felt organic to the novel. I had the multi-POV structure in mind even when the book was just a figment of my imagination.

The premise of the novel—the fact that each character has a secret they are too ashamed to share—required a structural container, so to speak, that granted the reader an omniscient view, a voyeuristic privilege, a chance to see inside each character’s mind. So while the characters, all stuffed in this cramped beach house for three days, are very much isolated from each other emotionally, the reader is privy to all their secret anguish. I’ve realized since that this kind of structure also mimics an aspect of the early years of parenting young children at home—the isolation of spending most of your time with nonverbal children and people you’ve just met (other new parents), but who you don’t really know.

I am still amazed at how seamlessly the point-of-view structure fell in place, although there were moments where I cursed myself for including so many perspectives. I’m a huge fan of television series. As a lifelong insomniac and nighttime knitter, I prefer series where I can watch one episode after another. I’ve learned so much about structuring novels from well-written and thoughtfully directed TV—delivery and order of information, how to create a gradual arc, sustaining narrative momentum, authentic character revelation, and more. Many of my favorite series—The Sopranos, The Wire, Six Feet Under, Battlestar Galactica, Breaking Bad, and Top of the Lake—employ the same multi-point of view structure, shifting from one character’s perspective to another. I’m sure my late night TV-watching addiction helped. But I don’t suggest it as a writing tool if you enjoy sleep.

In Leslie Jamison’s fantastic essay, “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” she talks about the pitfalls of writing about female pain. “You court a certain disdain by choosing to write about hurting women,” she writes. “When you bleed like that–all over everything, tempting the sharks–you get told you’re corroborating the wrong mythology. You should be ashamed of yourself. Plug it up.”

Did you worry that by writing about traditionally “female” topics, like relationships and parenting, that you might be risking your “literary cred”?

Did you worry that by writing about traditionally “female” topics, like relationships and parenting, that you might be risking your “literary cred”?

First, I have to tell you that I bought Leslie Jamison’s book today and am already enthralled.

THIS is the question I’ve been waiting to be asked. I’ve had the honor of being interviewed a bunch of times this past month, and I’ve felt myself trying to, with trepidation, approach this topic, and then scurrying away. As far as writing about “relationships,” I refuse to believe that any book, in any genre, and on any topic, is about anything but relationships. Every detail in life, every observation and interpretation we make, is filtered through relationships, or lack thereof. Any writer who thinks he or she is not writing about relationships is fooling him or herself. Sometimes that’s the game we have to play as writers. Making ourselves think we are writing about one thing as a way of avoiding the truth, all for the sake of getting through that first draft.

But writing about parenting—no, writing about mothers—that was definitely a risk, although I didn’t know this at the time. Now, I can say that I honestly can’t imagine writing a riskier book, that there is little that feels riskier than examining my own flaws and vulnerabilities as a mother and then sending them out into the world as a reflection of myself, even under the protective guise of fiction. So it was a personal risk.

I’ve asked myself: If you had known, as you were writing the early drafts, that the book would be published, would you have been so honest? I don’t think so. And that is the hidden blessing of that first publication. The honesty. The purity.

As far as professional risks, concerning my so-called “literary cred”—yes, when I finished the book and realized I’d wrote about parents, mostly mothers, I had an oh shit moment where I thought, Oh, my many childless literary friends are not going to like this book. What if they think writing about moms is uncool? I’m so embarrassed to admit this. I asked myself, Am I still a literary writer? What the hell does “literary” even mean? With time, and especially after I read what I’d written and felt proud of it, that question changed into an understanding that, maybe, my natural style, or at least the style I’m writing in right now, can appeal to both “literary” readers and more mainstream readers who are reading foremost for story and character, not just style. Genre labels don’t exist when you are in the deepest part of the writing, filtering your unique consciousness and perspective into a work you pray will move people. Maybe all the terms I’d been flinging around for a decade, as if I knew what they meant to me—literary, genre, chick-lit, women’s fiction—won’t matter one bit to the readers I hope I’ll be lucky enough to have. Once the book is in their hands, any label or genre pales in comparison to their reading experience.

Do you think it’s necessary–or even possible–to draw a clear distinction between literary and popular fiction? What do we gain when these lines are muddied, in your opinion? What do we lose?

I’m all for the muddying of categories, and find that the novels that stick with me are the ones that play with genre. We call them genre bending, genre transcending, genre breaking, as if they are smashing at the shackles that imprison them in one category or another, and I think it’s a just analogy. Some of my favorite genre-benders are books that are literary (they challenge the reader), but also have an element of science fiction or fantasy. A few of my favorites are Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, Geek Love by Katherine Dunn, and The Children’s Hospital by Chris Adrian. Others are novels that are both literary and suspenseful—Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Tana French’s Broken Harbour, and Megan Abbott’s Dare Me are just a few.

As a young writer recently pointed out to me, why is the “literary” genre the only one that is based on style instead of topic? Women’s Fiction, Thriller/Suspense, Historical Fiction, etc., aren’t styles after all, but topics. Sometimes, a label assigned to a book by the marketing team of a publishing house fits, and sometimes, to the detriment of sales, it does not. I understand and accept the need for those marketing labels in the increasingly difficult book-selling market, but I do think these labels often damage book sales, discourage writers and alienate readers. If a literary book is marketed as a thriller in the hope that the book will sell under that label, or given a book cover that promises the reader an experience the book can’t deliver, the inevitable result is disappointed readers. The author is at the mercy of the marketing.

When I started shopping Cutting Teeth around to agents and heard a few use the term “mommy book,” I had no idea what they were talking about. Yes, the characters were mostly parents to young children, but I’d been certain the focus was on the characters, their relationships, and their identities in relation to the world around them. When agents passed on the book, they often blamed it on the topic— “I’m not looking to represent a ‘mom novel’ right now” or “The market is oversaturated with mommy books.” And I thought, really? Because I hadn’t read many literary novels that focused on parenthood, and now I wonder if that’s because books about parenting are rarely marketed as literary, no matter the style. Unless they’re written by men—but that’s another story.

I was incredibly fortunate to find both an agent and an editor who took the book seriously. Almost, it seemed, despite the subject matter. And I was even luckier to have the book marketed in sync with my own perception of the book. Still, the doubt of my literary-ness had been planted. Was I, the founder of an organization of “serious” writers, a fraud for writing a book about “women’s issues”? Mothers to boot—the most vulnerable stereotype of womanhood? These doubts were a product of how I’d seen the literary world treat women writers I’d admired for writing about similar topics, no matter how literary their style. Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, for example, is what I’d consider a brilliant “literary” novel, written in a style and structure that challenges the reader, requiring him or her to be thoughtful as they interpret and decode meaning. The narrator is a wife and mother, and intelligent, even intellectual. Finally, I thought, a literary novel about motherhood that will be taken seriously! The book received some strong reviews, but not the critical attention it deserves. I was astounded by Michiko Kakutani’s New York Times review of the novel, where she dismisses the narrator by comparing her to “Debbie Downer on “Saturday Night Live,” and sympathizing with the narrator’s husband, asking “how he puts up with her willfully self-conscious observations… and tireless self-pity,” much of which Kakutani makes clear is related to the narrator’s challenges in young motherhood, and specifically to the emotions the narrator experiences as a result of those challenges.

When I hear critics and writers, often women, criticizing women writers for writing about “women’s topics,” which is code for relationships, which is code for emotion, it confuses me. Are the criticizers trying to lift themselves up to that pedestal of “serious writing,” historically the turf of male writers, by stepping upon the backs of other women? I am ashamed to admit that ten years ago, I probably would’ve had the same criticisms. I remember how, in a seminar when I was getting my MFA, I trashed a published literary novel written by a woman and commercially popular. I called the book sentimental and “cheesy.” That book is now one of my favorite novels. How naïve I was, but also insecure, and I wonder if my showy disapproval was an attempt at distancing myself from what I’d learned, in workshop, was way uncool—emotion. Now I can look at that younger version of myself and see that she was protecting her own “literary cred” by cutting down another writer who was brave enough to reveal emotion in a subtle but affecting way.

Parenthood is an emotionally heightened time. Would any parent admit to it being anything but? I’m not talking about the saccharine-sweet joy you see in diaper commercials, though there are those moments, but also the self-doubt, fear, pride, fierce defensiveness and disappointment that makes a new mother or father reexamine their identity, and their perception of her or himself. Are there moments of sentimentality and melodrama? You bet. I caution my writing students, many of whom are wary of revealing even a hint of emotion, that emotion is louder on the page than in real life, and that subtlety is important, but avoiding emotion in literary writing, and criticizing other writers for taking risks with emotion, is damaging to literature as a whole. This avoidance of emotional revelation by literary writers is a mystery I’ve thought of often in the last ten years, and which I wrote about in an essay for The Millions about emotion and sex in literary fiction. Why are literary writers so wary of revealing emotion? Do they fear that a novel written in carefully crafted prose that challenges the reader, when infused with genuine emotion, when risking (not achieving) sentiment, might magically turn, like Cinderella’s pumpkin coach, into a chick-lit novel? Emotion is universal to all genres. Every author is human after all.

What are the themes and questions you’re most drawn to writing about? What do you return to over and over again?

Fear. Fear. Fear. Emotion. Obsession. Insecurity. Self-loathing, which often appears through a filter of humorous self-scrutinizing. The quest to know and accept one’s self. The search for a home, whether that is learning to accept one’s self or finding a community that accepts you. Existential anxiety, which is most likely a side effect of the fact that I was raised in a devoutly Catholic home and then, as a teenager, lost my faith. In the end, I replaced that religious faith with my love for human psychology and emotion. Love. Love. More fear.

What’s the most helpful piece of advice you’ve ever gotten or given about writing?

I studied with Marilynne Robinson at Iowa and she taught us the importance of having compassion for your characters.

My own advice to writers:

– If it works, it works.

– In revision, imagine your reader’s experience. Your reader is a version of you living somewhere out in the world. Will the choices you’ve made create the kind of experience you want them to have? Will they feel and think what you want them to?

– This one is a bit hypocritical for a woman who runs a writing workshop: Only you know what is best for the “story” only you can tell. Workshop is most valuable in making you a more confident of reader and analyst of craft choices. Don’t take anything anyone says about your writing too seriously. Trust yourself.

– Lastly, do not fear emotion. It is the filter through which a writer delivers their ideas, themes, and unique perspective. Do not fear stepping to the very edge of that cliff that overlooks all that scary sentimentality and melodrama—the stuff your undergrad writing class instructor forbid you to reveal. If you don’t get close enough, your toes hanging over the edge, you will cheat yourself—prevent you from informing you of the story you need to tell. How can a story mean anything if it doesn’t make the reader feel? The writer must first feel that emotion if the reader is meant to. Prose can be precise, but emotion is most authentic when it is messy and contradictory and surprising, just as it is in real life.

You have a reputation among Brooklyn’s literati as something of a social media maven–a reputation born out by the fact that even the blog you created to help promote Cutting Teeth has made news. Parenting Confessional, the Tumblr created to accompany the book’s release allows parents to anonymously post their most closely guarded parenting secrets. Since its launch a few weeks ago it has been covered by The Guardian, among other outlets. This kind of self promotion is becoming a necessity for so many artists these days. Do you have any advice about how to do it well without selling your soul?

Authenticity is most important, which is a bit of a Catch-22 because if you don’t love social media the way I do, if you don’t need the unique interaction social media provides, using it to promote your work will feel anything but genuine—to you and your so-called audience.

I treasure the relationships I’ve made online and they are necessary to my social health. The sharing I experience online is fulfilling without feeling draining. It is socializing on my own terms. I can slip into a conversation, and slip out. I can logon, and logoff. This works for my slightly introverted personality. I can only handle socializing in small bites. And while the argument that critics make—that the relationships created online are superficial—might be technically true, they sure feel meaningful to me. Most importantly, these relationships are convenient. In my busy midlife years, when I am, in the words of Anne-Marie Slaughter, “having it all”—balancing professional success, a writing life and family, these are the relationships I have time for. All of this is to say that while I am clearly using my social media “platform” (I’m still not exactly sure what this term means) to promote Cutting Teeth, the relationships I created through social media weren’t intended for self-promotion. They were created because I needed the support. My social media friends cheered me on while I was writing the early drafts of Cutting Teeth, comforted me after rejections, and I do feel as if Cutting Teeth is partly their success, as well as mine.

Obviously, not many people have this mad love affair with social media, but I do think that every writer, artist, person who has work to share/promote, has to find his or her way to be authentic online. There are writers who do not share personal day-to-day anecdotes, but, instead, share their favorite inspiring literary quotes, or essays they found stimulating. I love author Ellis Avery’s unique use of social media—she shares a daily haiku that describes her observations of daily life. Focusing on a different part of your life—your knitting, your photography, your reading list, your antique collecting, this list is as endless as our interests—is a great way to give a subtle sense of your unique personality without crossing the boundaries of privacy that more introverted personalities might need.

Still, it is an incredibly intense, and occasionally overwhelming experience, especially for a first-time author. Writing is a very private act. Publishing is very public. The new expectations that both readers and publishers have for the relationship between writers and readers is full of Facebook and Twitter chats, online Q&As, blog tours, secret-revealing personal essays, and Goodreads reviews. Writers see reviews of their books constantly, and are expected to respond. I’m just starting to enter this phase of the publishing experience since Cutting Teeth was just released—fingers crossed that my honeymoon with social media remains untarnished as I move forward.

What’s up next for you? Do you have another novel in the works already?

Yes, I do, and I’m very excited about it.

The working title of the novel is The Gypsy Moth Summer and the narrator is a woman looking back on the summer of 1993—the summer that a tragedy changed both the narrator and her suburban Long Island town. It is a novel about class tension, racism, teens behaving badly, and the pressures young women face as they struggle to create their identity in a town where corruption lies just under the surface. A terrible accident takes place and a cover-up is attempted. When the cover-up is exposed, the narrator must choose between her town and her dignity. The novel is inspired by Alice McDermott’s That Night, with a dash of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides. Dark, psychological, and atmospheric—I’ve wanted to write about the catastrophic effects of suburbia’s dark secrets for years.

Love this article! Julia Fierro makes many of the same points about ‘chick lit’ (masquerading as ‘mommy books’) and about literary fiction that Jennifer Weiner does. Perhaps Fierro’s comments will be taken more seriously than Weiner’s? The more authors, male and female, who realize than everyone is writing about relationships, when you get down to it, the better!