A screening of ‘Paris is Burning’ sparked a heated debate on Facebook when readers learned that members from the ballroom community the film represents would not be presenting. Image: Miramax

As of today, over 7,000 people have RSVP’d yes for Celebrate Brooklyn’s screening of Paris is Burning, the famous documentary that explored ball culture in 1980’s New York. By comparison, only 1,384 people have RSVP’d for Krosfyah, the celebration’s second most attended event, and just 179 people have accepted invitations for Lucinda Williams. Normally, this would be cause for Celebrate Brooklyn to celebrate itself, but over this past weekend, their Facebook page exploded in anger. While Paris is Burning examines ball culture produced by Trans /Queer People of Color (TQPOC), all of the presenters listed on the bill for that night–including director Jennie Livingston and DJ JD Samson–were white. None were from the Ballroom community.

Both BRIC, the event’s producer, and Livingston have since posted statements in response, and Samson has pulled out. On Facebook, the artist announced that, in addition to withdrawing, she has since “urged the programmers to add queer poc and/or trans poc to the bill.” As some readers announced that they would be boycotting the show, including an official petition from local activists, BRIC published an apology today, in which they stated, “We have now done what we should have done when we initially planned the event: reached out to QTPOC organizations and individuals, and members of the ballroom community, to gain their insights and hear their ideas for the program. We apologize for not having done so earlier.” In the days preceding this statement, reactions from Facebook were characterized by equal parts despair and disbelief. From a petition* written collectively and issued by #ParisIsBurnt: “This is the appropriation of our narratives for the sake of entertaining a gentrifying, majority white audience” to DJ Tikka Masala: “I don’t understand how it could go unnoticed [by Celebrate Brooklyn] that the film had a contentious history within the New York Ball Scene or that no queer people of color or folks from the current ball scenes were involved.”

At the time of the documentary’s release, critics at publications like The New York Times and The Washington Post called Paris “unsentimental” and “eye-opening.” Paris introduced words that mainstream audiences now accept as dictionary-definition vocabulary– Queens, Realness, Balls, Throwing Shade. As audiences, we met Venus Xtravaganza, Willi Ninja, Octavia St. Laurent. They were brilliant performers, skillful leaders, and complicated people. They were also compelling storytellers who struggled with AIDS and societal rejection, who told poignant stories about building houses as they were forced out of homes.

But some critics–including Bell Hooks, and some of the movie’s protagonists–weren’t nearly as enthusiastic. The film grossed $4 million at the box office, not a large sum given the size of the industry, but a strong performance for a movie that cost $500,000 to make. Then each of the film’s performers, with the exception of Willi Ninja and Dorian Corey, sued Livingston, arguing that she had misled them about their potential for profit. Pepper LaBeija, one of the film’s stars, argued that while she “loved the movie,” “she [Livingston] told us that that when the film came out we would all be all right. There would be more coming.” The subsequent fallout was brutal, and fell along all-too-familiar racial lines. While Livingston, who is white, went on to become a documentarian, so many of the film’s stars, who are people of color, remained stuck right where they began–in poverty. Many of these performers later died (from AIDS and AIDS-related conditions, murder, and other causes), as the film racked up awards worldwide and received an absolutely predictable Oscar snub.

The feeling of exploitation has only continued to burn, right until BRIC announced the show, nearly 25 years after the film’s release. An event celebrating Paris is Burning–featuring one white director, one white DJ, and zero people from the ballroom scene–stung, and stung hard. Poet and educator J Mase III told me, “Paris Is Burning has made speaking opportunities and dollars for the white bodies behind the camera, but left little to the black and brown, trans and queer folks whose history, stories and work made space for so many.” Journalist and transsexual/intersex advocate and coordinator with Black Trans* Women’s Lives Matter Ashley Love, shared** poetry on the event’s Facebook page forcefully arguing that “reparations must be made.” Love continued in a separate post: ” . . this gay/white washing of transsexual and TQPOC history is nothing new and is not an isolated incident. The month of June did not start off as a white gay and lesbian house music party that charged an entrance fee that many POC folks could not afford, it started off as a riot originated by poor TQPOC folks that had had enough of white supremacy, transphobia and police brutality.”

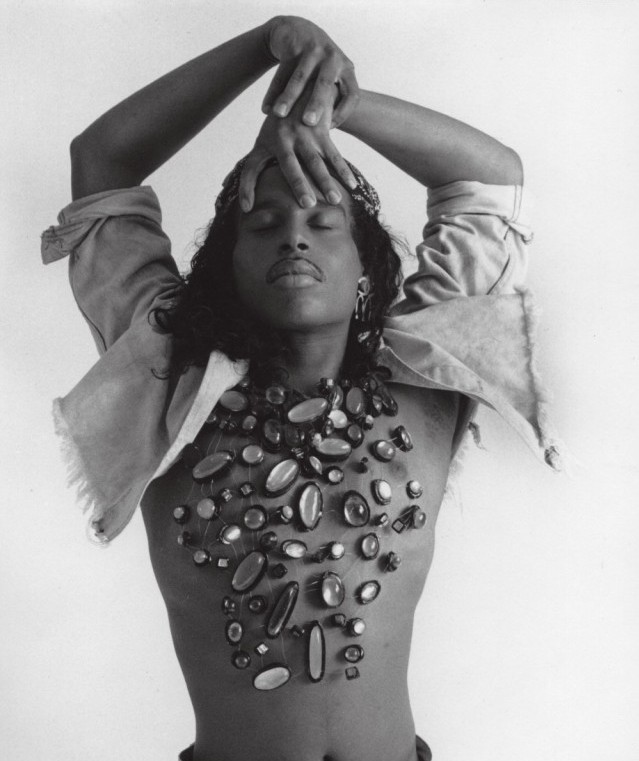

Willi Ninja, a legendary ballroom performer who was featured in Paris in Burning. He passed away in 2006. Photograph courtesy of Voguing: Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-92

In a separate comment on the page, Jazmine Perez, who’s been active in the ball scene for the past twenty years, having competed in many categories, and is Mother of the House of Manolo Blahnik (New York chapter), wrote, “I can say that as long as I have competed at balls (Mother Revlon NYC 18 years), I have never seen Jennie Livingston. I don’t know what she looks like! And that’s sad because at the end of the day Jennie Livingston did capture the essence of the time and the people she shot opened their lives and hearts out to her and the world . . . I understand she is under no obligation to continue a relationship with the ball community, but she should recognize and pay homage to the community that got her where she is at today.”

Afterward, when reached by email, Perez praised the film but lamented its ultimate impact: “I think Paris is Burning depicts and beautifully explains the culture and the atrocities LGBT POC face . . . Unfortunately, though this film created that awareness and catapulted the community to the rest of the world, sadly no social change has happened since.”

At this point, Celebrate Brooklyn is in the midst of creating a new line up, expected to be released in the next couple of days. Compared to many New York music festivals, the series does strive to keep their events affordable and inclusive. But however genuinely unintentional their error was, I will not be attending an event featuring all-white people talking about an art form imagined, produced, and sustained by people of color. I wish I could say that Celebrate Brooklyn’s mistake was an isolated case, but sadly it’s rooted in a history of cultural appropriation.

A while back, actress Amandla Stenberg reiterated a popular question posed on social media: “What if Americans loved black people as much as they loved black culture?” The original tweet was under 140 characters, but it spoke to larger themes of appropriation. Cultural erasure. Exploitation. Events celebrating art made by artists of color, but presented by white performers, to often all-white crowds. BRIC’s decision to go forward with the show with no TQPOC performers felt all too symptomatic of this history, and of a gentrified Brooklyn. It sparked a bloody discussion because it hit a bleeding wound.

My feelings about the film itself are slightly more complicated. I grew up loving Paris is Burning, even as I question it. To be clear, I’m a queer white cis-woman, and in many ways, an outsider, looking in at stories that don’t belong to me. At one point, I used to coach (“coach” is a word I use lightly. Let’s substitute: “order pizza for”), the vogue team at the high school where I worked. I can’t help but think that the film’s incredible mainstream success helped to pave the way for the success of the art form both internationally and here in our city (except when pop stars are profiting from it). Every day, I came to a high school where I heard the word “faggot,” sometimes as many as twenty times a day. But inside the school auditorium was my student, voguing, walking, and shouting lines of dialogue from Dorian Corey into the microphone. “She is my hero,” my student told me, the reason he walked despite rejection. Good feelings don’t excuse wrongdoing, but either way: the memory was there. The lines were remembered, the story stuck. He walked.

Where do we place the blame? While Livingston made the documentary, the film belongs to a larger culture of filmmaking that enables these kind of disparities in the first place. Historically, documentary directors get paid, while documentary subjects get exposure. It’s a miserable trade, but also standard practice, and one grounded in a journalistic code of ethics. After the lawsuit was dropped, approximately $55,000 was distributed among 13 performers (Jennie stated that she had planned to distribute payments prior to the lawsuit). While documentary subjects don’t traditionally get paid, the disappointment felt by performers was palpable: “What hurts is that I’m famous but not rich,” Pepper told The New York Times.

Still, many of the criticisms of the film aren’t aimed at the industry, but at the director herself. Comments on Facebook have ranged from the virulent: “Livingston is nothing but a disgustingly structurally racist trash bucket,” to the protective: “I came from the ballroom scene . . . the Jennie Livingston I know came to visit our mutual friend Willi Ninja in the hospital just before his death,” to serious inquiries about how the director profited from the story. Patti Sullivan, a screenwriter and friend of Jennie’s, told me the following:

“How much of that four million did Jennie Livingston really get? Not much. Miramax got a lot of that money. A lot of people tell the narrative that when the film ended she became this big documentarian and left everyone else behind. But it’s not like her star really rose and she had this stellar career. She’s been toiling ever since, always struggling to put something together. She was completely ignored by the Academy. Look at her IMDB. Paris is Burning is famous, but it’s not like it launched this huge career for Jennie. It should have. Why didn’t it? Because she’s queer and because she’s a woman.”

Yet it’s not just the money made from the film that’s divisive, writers have stressed. It’s the feeling that Livingston has since abandoned the community that gave her a name. As Jazmine explained on Facebook: “When we view documentaries we are touched by them and want to know how we can help . . . her presence is needed and wanted!” The change petition calls upon the director to make amends: “Use the platform that you’ve gained through our stories to speak out against the atrocities that are killing us daily. Violence against trans women of color specifically, like the still unsolved murder of Venus Xtravaganza, is still rampant. Share your limelight . . .” The issue, it appears, is bigger than money–it’s consciousness.

But documentary history, particularly social-issue documentaries, is full of documentarians who made their films, and then quietly, moved on. Steve James, behind Hoop Dreams and The Interrupters. David France, who directed How to Survive a Plague. Joshua Oppenheimer in The Act of Killing. Eugene Jarecki and The House I Live In. While each of these directors has remained active in filmmaking and social justice filmmaking, they haven’t initiated large-scale foundations, and the majority have moved onto other projects, other subjects. Yet media criticism of each of these (male) directors is surprisingly muted, especially in comparison to Livingston. Why?

The controversy behind Paris is Burning raises important questions about race, class, and even storytelling. At what point does a director/storyteller’s job end? Once the movie is released in theaters, and streaming on Netflix? Or far later, after substantive change has been made? Documentary journalists almost always pick the former, but that doesn’t lessen the hurt felt by the subjects left behind. It’s difficult for a storyteller to know when to end a story when its plot, and its pain, feels endless.

In a statement posted early this morning, Jennie wrote: “The movie was made, above all, to raise consciousness and to convey the greatness of the people in the film, so thank you for reminding me the extent to which I need to keep listening deeply and acting as a visible and supportive ally to TQPOC people and struggles. . . Movies are magic, and when we don’t get to see our beauty and fierceness in all its glory, we may forget who we are and why we matter. That’s what the screening on the 26th was–even as BRIC erred, and as I erred–meant to be. ”

BRIC is expected to change its lineup, but as the event currently stands, I won’t be attending Paris is Burning because of my serious concerns about representation. I’m anxious to see if BRIC is to able to substantively change the event so that I can come to celebrate performers from the current ball scene, who deserve creative rein to curate the show that’s supposed to be representing them. The story here is bigger than one event, though. This is a long conversation that began years before Celebrate Brooklyn announced their lineup on May 7th. It’s painful and it’s difficult, which is exactly why it should continue.

*The original article attributed the quote to Imani Henry. It is actually from a petition written collectively and issued by #ParisIsBurnt. We apologize for the misattribution.

**The original article wrote: Journalist/transsexual/intersex advocate and coordinator with Black Trans* Lives Matter Ashley Love. It should have read Journalist and transsexual/intersex advocate and coordinator with Black Trans* Women’s Lives Matter Ashley Love. We apologize for the omission.

This is a little harsh. Documentary filmmakers are not Michael Bay, nor Peter Jackson. They’re lucky of they make a livable fee from their work and looking at her IMDB page, she’s probably living from fellowship to fellowship after selling one limited release low-budget film to a since-bankrupt indie studio twenty-five years a ago. They are essentially journalists and their work often includes years of shooting, editing, research and intensive fundraising (to cover just the scrappiest of productions). It’s often an ongoing battle to cover the high cost of filming from one day to the next, so the filmmaker has to do triple or quadruple duty themselves, arriving hours early on location to deal with the minutiae of lighting, sound, etc. Of course they deserve to be compensated for their work and with a few very rare exceptions, Morgan Spurlock and maybe a unicorn, most are just barely making a living to support themselves and her family (and often perform other jobs to make ends meet). Moreover, her role is as a filmmaker. She is not a social worker, not a doctor, not anything else. She created an admirable contribution to society by widely telling the story of an extremely underrepresented community that no other journalists were touching at the time. And that’s something good journalists do. They create a new a dialogue that ideally sparks tolerance and/or social action. That’s the extent of their job for better or for worse. I can assure you that even the creators of Hoop Dreams (pop quiz: how many people can name the directors of the most influential documentary of all time?) aren’t living high on fortune and fame.

You raise great points, but I encourage you re-read the piece. My point wasn’t so much to suggest that Livingston needed to pay her subjects because all subjects get paid. I wrote: “documentary directors get paid, while documentary subjects get exposure. It’s a miserable trade, but also standard practice, and one grounded in a journalistic code of ethics.” I understand why directors do what they need to do, but I feel empathy for their subjects)

I was, however, sympathetic to the legitimate concerns raised by the protesters that the director purposefully misled them into thinking they were going to get paid. Not paying your subjects? Ethical. Lying to your subjects and telling them that they will get paid? Absolutely unethical. The director was sued by 13 of her participants, claiming that she had done the latter. Two protagonists claimed otherwise, as did Livingston. Notice that I didn’t take a stand one way or another (evidence is mixed), but rather, brought both sides of this painful story to the surface: “After the lawsuit was dropped, approximately $55,000 was distributed among 13 performers (Jennie stated that she had planned to distribute payments prior to the lawsuit).”

Lastly, I never asked the director to perform miracles. Of course she did the world a good by producing this film. Amazing. But consenting to go on stage without the people she’s claiming to represents? That hurts. The situation is complex, and I strove to reflect that complexity in my language: “It’s difficult for a storyteller to know when to end a story when its plot, and its pain, feels endless.”

These aren’t directives. They are questions and expressions of empathy.

I wish there was a tl:dr for this commentary. I will admit that i couldn’t make it past the first line because of the claim that more than 7000 had rsvp’d to attend the screening. Just because someone joins a Facebook group doesn’t mean they are rsvping for an event. Once I read that, I knew I would question everything you wrote and opted out.

If you didn’t read it, then you probably shouldn’t comment. No, I’m sorry, then you shouldn’t comment at all.

Anyone tempted to slog through what in retrospect appears to be some sort of performance art rather than a fair summary of events or justified polemic should [know]… All that matters is that a small clique of angry internet “activists” have hijacked a needlessly contentious error in protocol in order to further extort cash from a documentarian who has already been bled dry because she became too close to her subjects and compromised her own ethics by paying them kickbacks after the first round of character assassination over 20 years ago.

Editor’s Note: This comment has been edited for clarity and kindness.

At the risk of being further “edited for clarity and kindess” (both Orwell and Foucalt are spinning in their graves), this is the first (and hopefully last) magazine/journalism/literary website I have ever encountered where the author/editor moderates comments in such a thin-skinned and passive aggressive manner. However, upon reflection, it does reflect the style and tone of the article. Brooklyn hipsterism…sigh.

Bled dry? You do realize that every person in the documentary is dead, and died poor, right? And those “angry internet activists” that you wrote off are from the same community that is featured in Paris Is Burning — trans, queer, Black and Brown. Then again, you already smeared those subjects by saying that they extorted money from the director, so it’s clear that you don’t give two shits about their exploitation. Check yourself, take a seat, and stay seated.

As a fan of Paris Is Burning and as a fan of documentary films, I feel the need to speak up. It is clear that Heather Dockray does not understand the documentary industry nor its economics. It’s a shame if people think Livingston got rich off of the film and moved on and it’s good the Dockray defends her. I can’t speak to all the filmmakers she lists, but Steve James and Joshua Oppenheimer did not turn their backs on their subjects and “move on”. No, they did not start “large-scale foundations” because they are FILMMAKERS! If they’re not actively making a film, they are finding partnerships, funders, other networks to build coalitions to make the next film. If these filmmakers had the means, the capital, the support to start a foundation for every single film, I have no doubt they would. However, the documentary world still recognizes and applauds their social issue activism through BritDoc’s Impact Awards. In 2013, Act of Killing won the Impact Award for the change and impact that the film made – http://britdoc.org/uploads/media_items/theactofkilling-web.original.pdf. The Look of Silence has continued the conversation about the atrocities of the Indonesian genocide. THAT IS NOT “MOVING ON”! The Interrupters was nominated for the Impact Award the same year as Act of Killing – http://www.britdocimpactaward.org/files/theinterrupters.pdf. And why was Steve James inspired to make The Interrupters to begin with? In the years following Hoop Dreams, Arthur Agee and Will Gates both lost loved ones to violence. How does a filmmaker respond, he makes a film about violence in the very community that took those loved ones. Nearly, every high school student in the City of Chicago saw The Interrupters. Church groups, the Mayor’s Office, after school programs. In fact, just this week Chicago Bulls star Joakim Noah was awarded the NBA’s Citizenship Award for his work with at-risk youth. Why did Noah get so heavily involved with Chicago’s at-risk youth? He watched James’s The Interrupters and befriended one of the film’s stars Cobe Williams – http://www.noahsarcfoundation.org/blog/?news=raise-your-voice-the-chicago-bulls-center-shines-the-spotlight-on-inner-city-kids

So while the filmmakers may not be running a “large-scale foundation”, the films continue on as tools for those who need it the most. It continues to inspire and create a movement.

Also, of the other films and filmmakers mentioned by Dockray, The House I Live In won the Impact Award in 2014 – http://www.britdocimpactaward.org/files/thehouseilivein.pdf

These filmmakers are not humanitarians like Steven Spielberg or George Lucas because they are not wealthy. They simply make a living. Dockray is quick to point out that Miramax took a big chunk of the box office from Paris Is Burning, but she has no clue about the economics of these films, how many other funders get paid before the filmmakers. Besides, looking at the box office numbers of these films, how could they start “large-scale foundations”?

The Interrupters – http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=interrupters.htm

Act of Killing – http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=actofkilling.htm

The House I live In – http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=houseilivein.htm

So to answer your question, “At what point does a director/storyteller’s job end?” For those who are truly social issue filmmakers, the job never ends. That’s why the best of them never truly “move on”.

I believe you misunderstand the language of the piece. In response:

My question I raised about “when a storyteller’s job” ends wasn’t so much a directive as an open-ended question (I wrote: “At what point does a storyteller job’s end?). At what point should a director stop advocating for their subjects? I certainly don’t know, but I have to hope that’s it at least slightly beyond the point when it’s released to theaters. Of course, people have to move on. But that doesn’t lessen the pain for people still enmeshed in the problem (I wrote: “lessen the hurt for subjects left behind.”) You saw this is as an attack and a list of demands, but the tone I strove for was one-part questioning, two parts empathy.

I brought up the point about the other directors, only because the criticism directed at Livingston was so disproportionate in relation to criticisms I’ve heard about other directors. Take a look at the event’s Facebook page. It’s virulent. Livingston has been criticized for YEARS for leaving her subjects behind. Other directors (like Steve James) haven’t. That’s not at all justify their criticism, but instead raise the really important question – why HER and no one else? My words were chosen incredibly carefully: “Yet media criticism of each of these (male) directors is surprisingly muted, especially in comparison to Livingston. Why?.”

Prior to becoming a journalist, I spent years as a social worker. So I’ve been on both sides: both as a social worker, watching the way my students and clients felt as people came in, told their story, and moved on. And as a storyteller, who also told their stories, tried to continue to advocate for them, but struggled with time, money, and other priorities, to do it.

This is a painful story. You saw them as demands. Re-read. These are questions.